Scapular Stability & Mobility: A Key to Avoiding Rotator Cuff Injury

A little twinge when you go to brush your hair, a big catch upon trying to take your bra off, tenderness and overall achiness during sleep—these are all possible signs or rotator cuff injury (RCI). This is one of those injuries that even those that have an active lifestyle can find themselves with. As a matter of fact, being active and doing a lot of overhead arm actions can help speed up the arrival at RCI.

To understand how scapular mobility and stability is one of the most crucial components for keeping your rotator cuff well, let’s get familiar with some anatomy. The rotator cuff consists of four muscles, along with their tendons, that stabilize the head of the humerus in its socket, the glenoid fossa. It is helpful to know that the glenoid foss is part of the scapula. An easy way to remember the rotator cuff muscles is with the acronym SITS. The supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis create force couples that keep the humeral head from translating too far anteriorly/posteriorly, and superiorly/inferiorly. They are the stabilization system of the shoulder (glenohumeral) joint.

While the SITS are the deeper stabilizing muscles of the shoulder, they lie deep to more superficial muscles that support the movement of the arm bone and scapula. In the picture here, you can see the deltoid, which is the most superficial shoulder muscle that you can typically see and feel in your body.

The scapula, or shoulder-blade, has 17 muscles attached to it! That tells us that it was designed to MOVE and synchronize with all of the actions of the arm, elbow, wrist, and hand. For a few reasons, it is common for immobility to happen in the mid to upper portion of the posterior body. In other words, we tend to get stuck in the upper/mid-back and shoulder blades. One primary reason for this is seated, working at a computer posture. Visualizing a hunched forward position, the predominant effect in the upper body is arm bones forward and slightly medially rotated, and head in a forward position. Working for hours like this, day after day leads to the thoracic spine and scapular immobility. The scapulae literally forget how to slide along the rib cage.

While teaching scapular movements in my yoga classes, it becomes very apparent that this is not just a musculoskeletal issue, but a neuromuscular issue. The nervous system is highly involved. We can actually lose the motor skill to perform certain actions in the body. This is where patients and slowing down is key.

Moving your scapulae in all of their natural, ranges of motion is imperative. When the scapulae (and thoracic spine) lose mobility, the arm bone, wrist, and hand have to overcompensate to find ranges of motion needed to function in daily life. And then when we add exercise into this immobility, the rotator cuff (along with the elbow and wrist) often receives the brunt of it all. It is important to think in terms of mobility and stability. We need enough range of motion for functional movement, but we also need to maintain stability. This is especially key in the shoulder complex since it does have so much ability to move in many different directions.

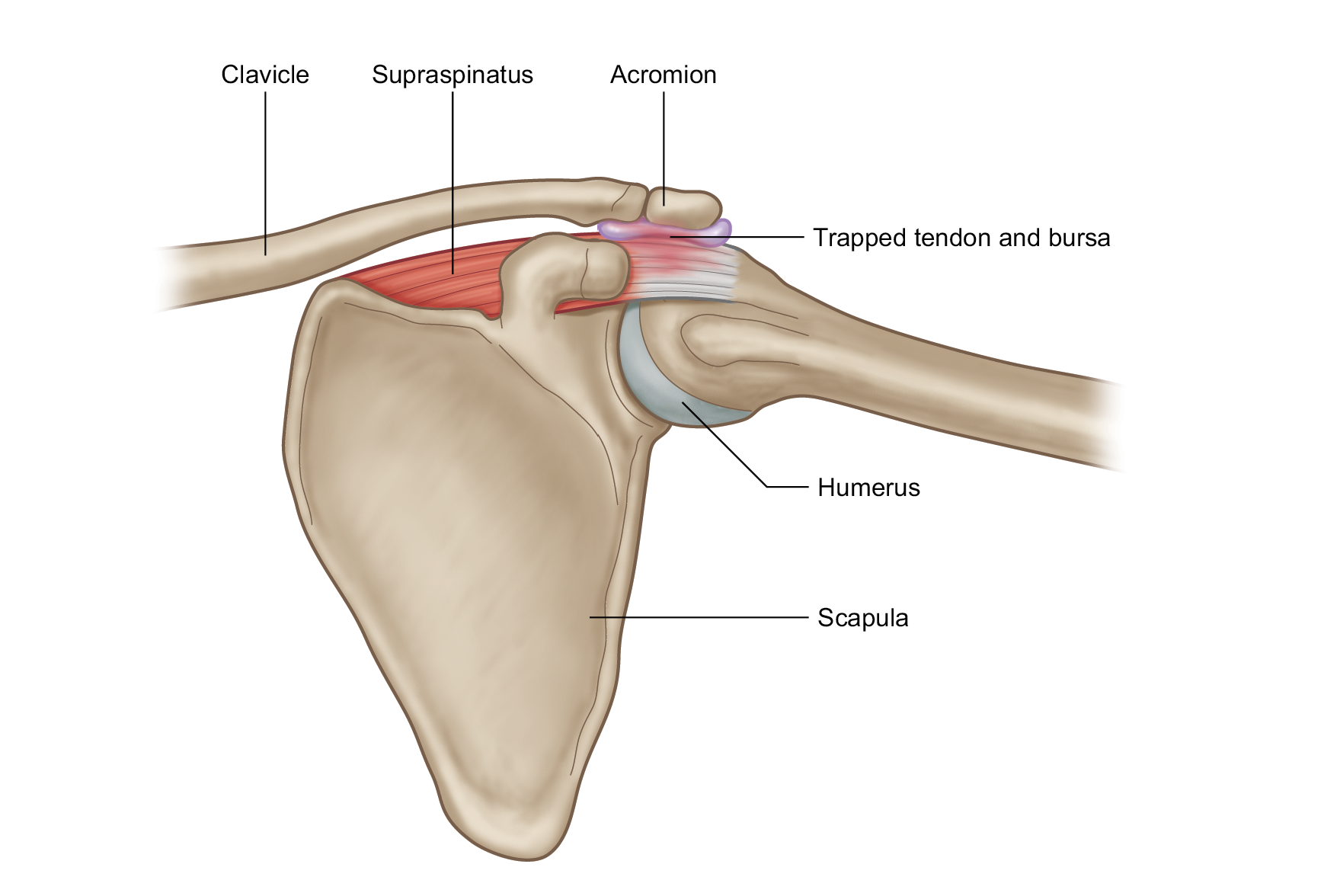

The area to be very familiar with when minimizing or rehabbing an RCI is the subacromial space. When the scapula isn’t synchronizing with arm movements, the subacromial space is compromised. This is crucial, because of the most commonly injured rotator cuff muscle/ tendon living in this space. The supraspinatus tendon is almost always involved in chronic rotator cuff pain and weakness. The subacromial space sits under the roof of the acromion process. The acromion is also part of the scapula. Imagine moving your arm up and down for years without the scapula also moving in concert with it. Whittling away occurs at the supraspinatus tendon. Also notice the bursa in the picture here. A bursa is a fluid-filled collapsed sac that provides protection in joint articulation spaces. Bursitis is a common occurrence when this space is impeded and inflammation happens. Bursitis can be present with our without degradation to the tendon.

I’m hoping that by now, you can see why it is imperative to maintain or regain scapular mobility and stability. To think in both perspectives, scapular immobility is the lack of slide-ability along the ribs. Lack of stability shows up in actions such as scapular winging. If the medial or posterior borders of the scapulae tend to lift or wing away from the body while doing weight-bearing, or in some cases, non weight-bearing upper-body movements, the scapula are presenting instability.

What to do? Work scapula movements in non weight-bearing, and weight-bearing positions. If there is an obvious weakness or injury, consulting with your health care provider may be imperative before doing certain exercises. If the motor-skill inaccessibility is apparent, as in it is hard for the brain to grasp these movements, it is a good idea to begin in non weight-bearing positions. The tactile instruction of a teacher or therapist can be a great tool to help the brain rebuild these kinesthetic maps.

Actions to work on:

Protraction: Sliding the shoulder blades laterally along the rib cage. The serratus anterior and pectoralis minor are the primary movers of protraction. For non-weight-bearing work, this can be done from hands and knees as in table-top position, or in a seated posture. Plank or high push-up requires protraction for stability. This is a great place to work it in a weight-bearing position. This can also be done with hands against a wall. To increase your kinesthetic awareness, get to know the prime mover muscles so that you can feel them activating with your movement.

Retraction: Sliding the shoulder blades medially along the ribcage. This is often cued as squeeze the shoulder blades together. Try to do this without backward bending. Our minds and bodies can trick us into thinking that we are doing a particular action when we are sneakily gathering a range of motion from elsewhere in the body. This can be done in many yoga postures. The scapulae naturally retract during a low push-up position, to gain more stability here, minimize lifting or winging by adding in a slight depression of the shoulder blades. For more non-weight bearing options, practice retraction in table-top position (cow pose), or in a seated/standing posture. Scapular push-ups on knees are a great way to retrain both protraction and retraction. The muscles of retraction of the middle and lower trapezius and the rhomboids.

Elevation: Lifting the shoulders towards the ears is elevation. Do this in lots of non-weight-bearing positions throughout your day. This is not typically an action that you would combine with weight-bearing. The muscles of elevation are the upper trapezius and levator scapulae.

Depression: Moving scapulae down and away from ears is depression. Do this in lots of non-weight-bearing positions. For weight-bearing work, Practice depression in low push-up positions. Remember that this will be in combination with retraction. The muscles of depression are the lower trapezius and pectoralis minor.

5. Upward Rotation: When you lift your arm above your head, the upward rotation should naturally happen. Two reasons why it would not: scapular immobility, or aiming to take “shoulders away from ears” as is taught predominantly throughout yoga. Fortunately, this narrative has begun to change. Can you see how taking your shoulders away from your ears during any overhead arm action would compress the subacromial space? For non-weight-bearing practice, let shoulders naturally rise when you lift your arms. For weight-bearing practice, allow the same action in downward facing dog pose. The muscles of upward rotation are the upper and lower trapezius and the serratus anterior.

6. Downward rotation: When arms return back down after being lifted, they naturally downwardly rotate. Tight upper trapezius can sometimes keep this from happening properly. The muscles of downward rotation are the levator scapula, rhomboids, and pectoralis minor.

A couple of added actions of the scapulae are anterior and posterior tilt. We can think of these more as natural actions that occur with functional mobility. However, a chronic anterior tilt of the scapulae is a sign dysfunction and lack of stability. The picture here shows the anterior tilt. This can occur from the forward posture discussed earlier, tight pecs, and weakened mid and lower trapezius, serratus anterior, and lats.

Improving stability and mobility of the scapulae is key to avoiding common shoulder, neck, and upper back pain. It can also be key to mitigating rotator cuff injury, along with possible degradation to the neck, elbows, and wrists. It will also be most effective alongside increasing thoracic mobility and releasing tight upper trapezius, latissimus, and pectoralis muscles. More on this later!

As always, I hope that this information helps you to move and live a little or a lot better in your own body. Simultaneously, I hope that tuning into the mechanics of your body helps to increase your over all ability to be mindfully aware in your life.

Thank you for reading. I ‘d love to hear your comments and questions.

Stacy

Stacy owns Yoga Project Studios with her husband Dave. She is the author of Embodied Posture: Your Unique Body and Yoga, which is a complete yoga anatomy text designed with bio-individuality and the healing aspects of embodiment in mind. She is a nutritional therapy practitioner, corrective exercise specialist, and studies orthopedic rehabilitation at A.T. Still University. She and Dave lead programs and trainings for teachers and students of yoga across the globe.

***All illustrations are from Stacy’s Embodied Posture book.